by John Souders

Waterford’s history with alcohol is long, complicated and often dreadful. In 1888 a village correspondent commented, “I hear the charge that there is a good deal of drinking in Waterford and I am afraid the town is not in position to bring suit for slander on this score.”

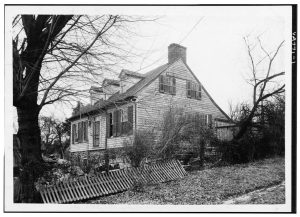

By the mid-1830s, according to Martin’s Gazetteer of Virginia towns and villages, Waterford boasted four taverns, outnumbering churches and schools. The tavern with the longest run operated at 40170 Main Street. It was known variously as Talbott’s Tavern, after lapsed Quaker Joseph Talbott, who bought the property in 1810; Manning’s Tavern; Matthews’ Tavern; and for long stretches the Waterford Hotel. Waterford Quaker Mary Dutton Steer probably had this establishment in mind in the early 20th century when she added the following stanza to her poem “Old Memories”:

A tavern stood upon the street

That some did much deplore,

For many a noble-minded man Went down to rise no more.

An early competitor was Klein’s Tavern, which owner Lewis B. Klein opened in 1825 as a “house of entertainment.” Its run as a tavern was relatively brief. The building today is known as the Pink House (40174 Main Street).

Around the middle of the 19th century, Oscar Fitzallen Reed operated a tavern in the center of town.

Thirsty Waterfordians also bought brandy and whiskey at any of several stores in town. And there were numerous instances of villagers, both Black and White, selling liquor without a license (see below). The results of all the drinking were predictable; they pepper the historical record. The press account below, from December 1865, is a vivid example.

On Tuesday and Wednesday of last week the County Court of Loudoun, sitting as an examining Court, was engaged in the trial of William H. Hardy and Charles Curry, for an assault on John P. Gregg, and robbery committed by them of one Gold Watch valued at one hundred and seventy-five dollars, one Gold Chain valued at twenty dollars, and thirty-five dollars in currency (commonly called Greenbacks,) consisting of three ten dollar and one five dollar notes . . .

Lieut. W.F. Keys,[1] late of the United States army, lives in Waterford, Loudoun county, was there on the night of the 8th of December, 1865, [where he] saw Curry and Hardy and Gregg, all warm friends of his, on that night. [Keys] was in his store when Hardy came in with Charles Virts and Gregg treated [them?] to cigars. Hardy was pretty drunk and commenced bragging about his shotgun, said it was the best gun in Waterford, in fact, the best gun in the County, and could out shoot any other gun. Gregg objected to the statement, and a bet was proposed. [Keys] Asked Hardy to drop it, as it was impossible for him to know whether this was the best gun in Loudoun, it was too broad an assertion. They asked him [Keys] to draw up a bond and he commenced to do so, and they urged him to do so; he consenting as he would do anything to get rid of them. Gregg immediately said he could get rid of him very soon if he did not want him. Hardy wanted Gregg to take back what he had said, but G. insisted that he had said nothing wrong.

Hardy wanted to fight badly, and took off his coat, and flung his arms about a good deal. Gregg also took off his coat, but after a good deal of wrangling, at Keys’ suggestion, put it on again. [Keys] tried to pacify them.

Gregg said he could whip the best man in Waterford, when Keys said hold on, you must not say so, when Gregg said he would take that back. Hardy continued quarreling and flinging his arms about, and Gregg, when he had his coat on his shoulder, said I can whip you with my coat on.

Hardy went out saying to Gregg, I can find someone who will dispose of you pretty soon. Shortly after he came back with Curry and [a] soldier of the United States army. Was about 12 o’clock that the whole row took place. Door [to Keys’s store] was open, Gregg staid there. Hardy came up to the door; Curry came in near the side of Gregg. Hardy said, “now John Gregg you damned rebel son of a bitch, I will settle your hash for you.” Gregg struck him and knocked him out of the door. Curry seized Gregg and they went down together. When I got out, Hardy was a little distance down the hill, with a stone in his hand, Gregg was on top of Curry, and the soldier on top of Gregg and struck at him twice. [Keys] Jerked the soldier violently off of Gregg, and then Gregg off of Curry. Young Howard Hardy came up and Wm. Hardy who had sidled round threw his stone, [supposedly] at Gregg, and it struck Howard, who threw his and struck William. This was done at his [Keys’s] door; he pushed Gregg in and locked the door. Hardy and Curry wanted [the] soldier to break the door, and [the] soldier wanted them to do it. [They] Called Gregg a damned rebel son of a bitch, and said he Keys, was harboring him. Looked into the store, saw back window open and concluded Gregg had gone, and let them into the store; they all searched for Gregg, but not finding him, commenced abusing Keys, and wanted to whip him. This witness [Keys] used a great deal of profane language and was ordered by the Court to cease using it.

W.T. McNully[1] testified that hearing a noise near Keys store, went up and found Hardy with a stone in his hand, in his shirt sleeves; soon after [he, McNulty] returned to Mr. Graham’s bar-room; which he keeps. Some fifteen minutes afterwards, Curry came with a soldier to borrow a pistol, which he refused to lend him; [he, Curry] was in the bar-room several times during the evening, and was pretty well intoxicated. This was about twelve o’clock at night.

John P. Gregg [was] examined [and] gave substantially the same statement that Keys did until he got outside of the door after knocking Hardy down, was in close contest with Curry and the soldier, one of them laid his hand on the hook of his watch chain, and he [Gregg] said that’s what you’re at is it? and knocked Curry down [and] from that time [he] became so excited, that he remembers nothing until he was again in the store, the door locked and violent attempts made to force it open. He escaped by the back door and retreated to the house of ——- two hundred yards distant; some time after returned to Dr. Fox’s office to have his wound dressed, and while there Curry and soldier came in threatening violently, demanding a [fight]. He being in fear of bodily harm and acting in defense of his life, knocked Curry down with a chair and thinks he bounded over him, and got out of Waterford; as he went out someone called halt, halt, several times, but he did not halt. Lost his watch, chain and money; watch and chain [were] recovered from the hands of a negro named Robinson by warrant from a Justice.

For [the] defense Henry Virts and Henry Hough testified that Hardy was pretty drunk, and Curry very effectually whipped. Submitted without argument. Both prisoners sent on to Circuit Court. Hardy bailed in $500, H.[enry] M. Hardy his father, [acted as] security. Bail was refused to Curry.

Whiskey seems to have been a very potent agent in producing this scene, as it is in almost all others.

[1] Pvt. [not Lieut.] William “S.” Keyes of the Loudoun Rangers lived after the war with wife Virginia at what became known as the Collins Cottage (no longer standing). William applied for a county liquor license in 1866, but in 1869 was fined a stiff $50 for selling without a license.

[2] William T. McNulty was about 17 at the time. He was living with his widowed mother at 40145 Main Street (Camelot School).

Loudoun County Liquor & Ordinary Licenses (Waterford)

Ordinary License 1852 Anderson, James S

Liquor License 1868 Berry, Newton

Liquor License 1847 Conrad, David

Liquor License 1867,1868 Hain[e]s, Joel

Liquor License 1866 Keys, William S.

Ordinary License 1824, 1827, 1828, 1831-1836 Klein, Lewis

Ordinary License 1837, 1838, 1851 Lee, Dodridge

Ordinary License 1848, 1849, 1854 Mathews, John

Liquor License 1852 Matthews, John

Liquor License 1901 Patton, M.H.

Ordinary License 1829-1833, 1835 Paxson, John

Liquor License 1849, 1850, 1854 Reed, Oscar F.

Ordinary License 1843-1849 Reed, Oscar

Liquor License 1867 Russell, James

Ordinary License 1840 Smith, George

Ordinary License 1856, 1858, 1859, 1860 Williams, Robert W.

Ordinary License 1851 Williams, J

Ordinary License 1861 Wine, George H.

Loudoun County Restaurant and Hotel Licenses 1856-1876 (Waterford)

Berry, Newton 1867 Taxed to Keep an Eating House

Haines, Joel 1867, 1868 To Keep an Eating House

Hough, Henry C. 1868 Eating House

Russell, James W. 1856 to keep an eating house

Russell, James W. 1866 to keep a hotel

Loudoun County Criminal Papers 1800-1899 (Waterford)

1790 McGavack, Patrick Selling liquor without a license. 2 counts

1800 Lacey, David Selling liquor without a license

1809 Patterson, Flemon Selling liquor without a license

1812 Lacey, David Selling liquor without a license Inn Keeper

1812 Sappington, John Keeping a Disorderly House Nov-1812 Listed as Inn Keeper

1815 Patterson, Fleming Selling liquor without a license

- Conrad, David Selling liquor without a license

- Bogges[s], Peter (Free Black) Selling liquor without a license

- Talbot[t], Joseph Selling liquor without a license Guilty

1828 Lacey, Sarah White Female Selling liquor without a license

1828 Minor, Nathan (Free Black) Selling liquor without a license Guilty

1832 Hough, Joseph Selling liquor without a license

1859 Densmore, William Selling liquor without a license

1859 Roberts, Lorenzo D. Selling liquor without a license

1869 Keys, William, Selling Liquor without a license Guilty $50.00 Fine

Bronwen C. Souders grew up in the American West and in a recent interview said her younger self found history “boring”. The past 50 years living near Waterford have changed her perspective. Now, as she used to say of her friend and mentor, historian John Divine, she is more familiar with the village of the 1820s than of the 2020s. This month’s interview with Bronwen focuses on the A.W. Phillips Meadow pastel, created by

Bronwen C. Souders grew up in the American West and in a recent interview said her younger self found history “boring”. The past 50 years living near Waterford have changed her perspective. Now, as she used to say of her friend and mentor, historian John Divine, she is more familiar with the village of the 1820s than of the 2020s. This month’s interview with Bronwen focuses on the A.W. Phillips Meadow pastel, created by