By Debbie Robison and John Souders

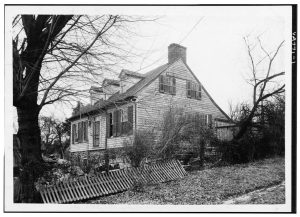

The simple one-room building on Second Street is the iconic symbol of Waterford’s rich African-American past. Black History Month is an opportunity to retell its story in light of intriguing recent discoveries.

For Waterford’s Black community, both free and enslaved, the prospect of education was one of the most prized results of the bloody Civil War; it was also a goal long supported by the local Quakers. Within months of Appomattox, 28-year-old Sarah Ann Steer had begun teaching under the auspices of her fellow Quakers in Philadelphia, where she had received training.[i] In September 1865 young Marie Matthews noted in her diary a trip in from her nearby farm to see “the Colored school held in Waterford.” She was favorably impressed.[ii]

Her reaction was far from typical in postwar Loudoun County, where former secessionists greatly outnumbered the Unionists who predominated in Waterford. The following January, a day after occupying Union forces had been shifted from Loudoun to Harpers Ferry, a minister from the Northern branch of the Methodist church was waylaid on his way from Leesburg to Waterford to preach. Three men in Confederate uniform put a pistol to his breast, saying “the damned Yankees have left now and you shall leave too.” The local agent of the federal Freedmen’s Bureau reported from Leesburg that in the absence of soldiers “it is the sheerest folly to keep an officer of the Bureau on duty here.”[iii]

Miss Steer was undeterred by such episodes. By July 1866 she was able to report to her school’s Quaker benefactors that “I have on my list 46 scholars all of them attend when they can, of the number 25 or 28 always present. They are mostly small children who can be spared from home. The larger Boys and Girls and Adults are obliged to work most of the time for their support and come to school when they have a leisure day or afternoon.” [iv]

Local historians have long supposed that Sarah Ann was teaching from her house—her family was then renting the Mahlon Schooley House (15555) on Second Street.[v] She regularly complained of the limited space available. A closer look at Freedmen’s Bureau records and Quaker correspondence, however, indicates that within a year she had begun to rent a small building from her cousin William B. Steer, a well-off elder of Fairfax Meeting. He had purchased Dr. Charles Edwards’ old house (15545 Butchers Row) in June 1866 and on the property, according to insurance records, was a one-story brick structure—possibly the doctor’s office—measuring 16 feet square.[vi] The size closely matches the Freedmen’s agent’s description of Sarah Ann’s classroom as of May 1867: “. . . there are now attending Miss Steer’s school about 25 Scholars all that there are accommodations for as the school is taught in a room not more than 14 feet square.”[vii]

By then the Freedmen’s Bureau was paying William Steer the monthly rent—$2.10—while the Association of Friends of Philadelphia continued to pay Sarah Ann’s salary.[viii]

The local Black community, meanwhile, had taken an active role in their education. In July 1866 “the Colored People of Waterford” purchased for $75 a vacant lot on Second Street from Quaker wheelwright Reuben E. Schooley and his wife Louisa (Lucy).[ix] They aimed to put up their own building to serve as both a school and church. They had selected five men to serve as trustees: Jonathan Cannady (Kennedy), Matthew Harvey, Alfred Craven, Henson Young and Daniel Webster Minor. “Web” Minor could read and write, but most of the others were probably illiterate. Craven and Young had been born into slavery.[x]

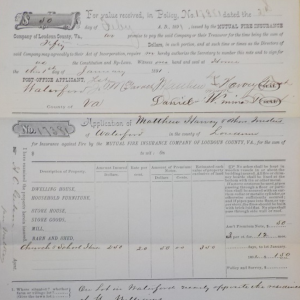

Money for the new building was, of course, an issue, even as construction began in early 1867. The Quakers appear to have chipped in, and the local Freedmen’s agent appealed to his superiors in May for $250 to complete the work.[xi] “. . . when the new house is complete [it] will seat and accommodate about 65 or 70 scholars, it will be filled to its fullest capacity, many can not now be admitted [in the rented space] for the want of room.”[xii] By then the building was already “under roof,” according to the trustees’ application to Waterford’s insurance company for coverage. The structure was “Made of wood and new, 24 by 30 feet with one brick flue when completed. One or two stoves.”[xiii]

The new building was still not ready for occupancy when Sarah Ann reopened school in November 1867, in the crowded rented room. But, she reported, during the summer break “the colored people [had] set themselves to work in good earnest to finish the house which is to serve the double purpose of a school-room and church. They had it plastered, the entire expense of which was borne by one man. They then had a church festival, the proceeds of which they devoted to putting in seats and a desk for me.”[xiv]

Curiously, in June the Freedmen’s Bureau had paid local White carpenter Charles Fenton Myers $100 for “service rendered in repairing [the] School house at Waterford.” The job had taken two carpenters 20 days to complete. “Repairing” on that scale seems an unlikely activity on a building still under construction. Perhaps the term was a bureaucratic fudge deemed more likely to elicit reimbursement from headquarters.[xv]

By the end of 1868, despite setbacks and delays, the students and Sarah Ann had settled into their new building. A visitor forwarded a glowing report to the Freedmen’s Bureau:

“. . . I came to Waterford where I remained over night & half a day visiting the colored people and their school and have the [honor?] and pleasure of submitting the following with reference thereto. There are about Thirty-five (35) families of (col’d) people in and about this village almost all of whom are said to be industrious and worthy people. Their advantages in this community are very much greater than in any other visited by me so far in the counties of Fairfax & Loudoun. Almost the entire white population being wealthy Quakers who interest themselves in the welfare of all the people without regard to race. The Teacher of the (col’d) school now in operation at this place is Sarah Steer she has enrolled about (30) pupills but a smaller [number?] in attendance. The salary of the Teacher is $35.00 per month Paid entirely by the friends of Philadelphia . . . Best school house in the county I believe is this one, owned with the lot of half acre entirely by the (col’d) people worth about $800, frame house good style & painted in size 25 by 30 ft in addition to all this they have now in their associations Treasury about $200 for educational purposes whenever needed, but thus far as I understand they have not been required to contribute any thing to the salary of the Teacher. It is only necessary to say in conclusion that if all the colored people in Virginia were as these are, with such white neighbors, ‘Peace’ would reign and reconstruction might be short work . . . But . . . Waterford can take care of its colored people or rather . . . they can take care of themselves.” [xvi]

That report was probably a bit over the top, but the 1869-70 session continued to build on earlier success, as the Bureau’s monthly report for February 1869 made clear:

“Waterford School opened October 1st and was expected to close May or June. The school was funded in part by the Friends of Philadelphia and part by Freedmen who contributed $15 this month. One teacher, 50 students enrolled: 35 male, 15 female, avg attendance 36. 24 students are members of the Waterford Temperance Society. Number in Writing: Books 36, Slates 20. Sabbath school with 6 teachers and about 40 pupils.”[xvii]

The Freedmen’s Bureau had pressed for establishment of a temperance society as an important feature of its support for the local Black community.[xviii]

The October 1869 report introduced a couple of cautionary points, noting that the school had been closed for five days “to make necessary repairs to the building,” and that public sentiment toward colored schools was “not very favorable though I think improving.” It was a period in which the political tides in Loudoun and the South were running against the reformers.[xix]

1870 brought big changes to the school. Virginia had a new postwar constitution—a condition for readmission to the Union—and with it a statewide public school system. The transition marked Sarah Ann Steer’s last year at the school. “In accordance with instructions received from Philadelphia, I closed my school March 31st.” She hoped “to be held in remembrance by those which whom I have been associated in this great work, a work in which my heart has been truly interested . . . .”[xx]

Under the Loudoun County school system, subsequent teachers at “Colored School A” on Second Street were African American. The school continued to be a source of pride in the Black community, and the trustees evidently retained a role in the management of the building, possibly receiving rent from the Jefferson District School Board for use of the building. By 1884 there was concern that the building was no longer adequate. The press reported in January that “the school trustees are going to build a large school house for a graded colored school.”[xxi] From the beginning the building had also served as a place for church services but had probably never been large enough for the purpose. In March 1885 “the members of the Methodist Episcopal Church (Colored) of Waterford . . . have no place now that we can call a house of worship, and the building we usually occupy does not accommodate the congregation.”[xxii]

In the end the congregants decided to build their own church, and the John Wesley Methodist Episcopal Church on Bond Street was dedicated six years later.

The plan for an enlarged schoolhouse was never realized. The Jefferson District School Trustees purchased a lot on High Street but never built the school and ended up selling the lot.[xxiii] Instead, a recent close inspection of the current structure indicates that it was at some point largely rebuilt. The wire nails used to frame the building, attach siding and interior paneling, and construct shutters, etc. did not come into use until well after the initial construction in 1867. And that siding is also not original; its cove-lap profile was not commonly used until the 1880s.

As yet, research has turned up no clear documentary evidence of reconstruction. Clues, though, appear on an insurance policy for the schoolhouse dated 1891, which shows that the schoolhouse, then in moderate repair, was still locally owned. At the top of the cover there is a second date, in red, of August 9, 1895. That may be the date when the insurance was discontinued, suggesting that a change occurred either in the names of local trustees or a possible transfer of ownership to the Jefferson District School Trustees. Ongoing research into insurance records, newspapers, and school reports is underway to narrow down the date of reconstruction, any ownership changes, and the reason for rebuilding the schoolhouse. Stay tuned.[xxiv]

In any event, the new building continued to serve the Black community of Waterford and its hinterland until 1957, when Loudoun consolidated its rural schools. The School Board sold the vacant structure to a private individual in 1966, and the Waterford Foundation acquired it in 1977.[xxv]

[i] O.S.B. Wall , Letter to Col S. P. Lee, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Superintendent of Education, M1913, Roll 45, p. 908, 17 Dec 1868.

[ii] John E. Divine, When Waterford & I Were Young, Waterford Foundation, 1997, p. 40.

[iii] Ferree to Fullerton, Act As. Cmr DC, Leesburg, VA, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Assistant Commissioner Files, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) M1055, Roll 5, p. 248, 15 January 1866.

[iv] Sarah A Steer, Monthly School Report, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Superintendent of Education, NARA M1056, Roll 14, p. 90, July 1866.

[v] Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County, Policy 473, 31 August 1867, Library of Virginia.

[vi] Loudoun County Deed Book 5V:335, 02 Jun 1866; Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County, Policy 231, 01 Apr 1869, Library of Virginia.

[vii] Smith to Manly Leesburg, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Records of Field Offices, NARA M1913, Roll 100, N495, 18 May 1867.

[viii] Smith to Lee, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Records of Field Offices, NARA M1913, roll 100, N194, 22 Mar 1867.

[ix] Loudoun County Deed Book 5V:334, 29 Jul 1866.

[x] Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County, Policy 17381, February 2, 1891; Loudoun County Will Book U, pp. 148 & 371

[xi] Smith to Capt S. P. Lee, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Assistant Commissioner, NARA M1048, Roll 5, p.219, 08 May 1867.

[xii] Smith to Manly, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Records of Field Offices, NARA, M1913, Roll 100, N495, 18 May 1867.

[xiii] Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County, policy #425, 27 Apr 1867, Library of Virginia.

[xiv] Friends Intelligencer, Philadelphia, PA, November 3, 1867

[xv] Charles F Meyers, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Records of Field Offices, NARA M1913, Roll 36, pp. 232, 234, 09 May 1867.

[xvi] O.S.B. Wall, letter to Col S. P. Lee, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Records of Field Offices, NARA, M1913, roll 45, p 908, 17 Dec 1868.

[xvii] Sarah A Steer, Monthly School Report, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Superintendent of Education, NARA M1913, roll 50, #821, Feb 1869.

[xviii] OO Howard, Circular letter to S P Lee, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, Records of Field Offices, NARA M1913, roll 048, p. 673, 23 May 1867.

[xix] Sarah A Steer, Monthly School Report, U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Monthly School Report, Superintendent of Education, M1053, roll 17, p. 434, Oct 1869.

[xx] Friends Intelligencer, Philadelphia, PA, 1870.

[xxi] Alexandria Gazette, Volume 85, Number 26, 30 January 1884, p. 2.

[xxii] Loudoun Telephone, Hamilton, VA, 27 Mar 1885, p. 3.

[xxiii] Loudoun County Deed Book 6V:15, 28 Aug 1883; Loudoun County Deed Book 7I:437, 20 Sep 1894.

[xxiv] Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County, Policy 17381, February 2, 1891, Library of Virginia.

[xxv] Loudoun County Deed Book 461:491, 31 May 1966 ; Loudoun County Deed Book 682:309, 19 Oct 1977.

Bronwen C. Souders grew up in the American West and in a recent interview said her younger self found history “boring”. The past 50 years living near Waterford have changed her perspective. Now, as she used to say of her friend and mentor, historian John Divine, she is more familiar with the village of the 1820s than of the 2020s. This month’s interview with Bronwen focuses on the A.W. Phillips Meadow pastel, created by

Bronwen C. Souders grew up in the American West and in a recent interview said her younger self found history “boring”. The past 50 years living near Waterford have changed her perspective. Now, as she used to say of her friend and mentor, historian John Divine, she is more familiar with the village of the 1820s than of the 2020s. This month’s interview with Bronwen focuses on the A.W. Phillips Meadow pastel, created by