By Elise Bortey

It’s difficult to say when African Americans first came to Waterford, but we do know that in 1758, there was at least one enslaved person in the area. By the end of the eighteenth century, a few free African Americans had established residency. Because Waterford was largely a Quaker community and Quakers did not believe in slavery, it is believed that freed African Americans were drawn here. However, this didn’t mean non-Quakers in the area held the same sentiments towards slavery. While in 1810 there were 24 freed persons that resided in Waterford, there were also 11 Black enslaved people.

When Africans were brought to America, they continued to follow their beliefs and traditions as much as possible. White Christian slave owners tried to suppress their cultural beliefs and forced them to attend Christian church services. The teachings were a way for slave owners to gain more control over their enslaved, introduced under the guise of religion. They interpreted the Bible in ways that justified slavery. Throughout much of the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, Christianity began to take hold and replace much of the African religious belief system. African Americans embraced Evangelicalism and started forming their own churches. This enabled them to have more power over their own beliefs and interpretations of religious texts.

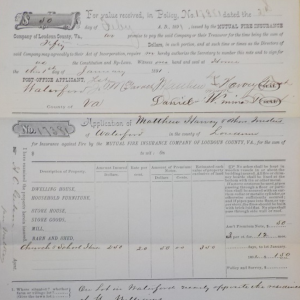

The primary Evangelical branches African Americans embraced were Methodist and Baptist churches. In 1867, the African American community of Waterford established the John Wesley Church, a Methodist church, in the building now known as the Second Street School. It was named after an Anglican clergyman, who was the founder of Methodism. When the congregation outgrew the small schoolhouse, they sought property to build a larger church. With the help of the white Methodist churches in the area, the John Wesley congregation was able to raise enough money to buy the Hough property on Bond Street, approximately a half a mile north of the Second Street School and near the Waterford Mill. There, they built their own church. They began building in 1889 and finished sometime towards the end of 1891.

As of 1910, the church had a thriving, active membership consisting of 25 Black households residing in town. It was used both as a place of worship and as a central location for social gatherings. The church had an active charitable congregation that would regularly sponsor fundraisers, community picnics, and special events for children to enjoy.

The Waterford Foundation commissioned a Historic Structure Report in 2018 to document the history of the church structure. By observing the existing structure and comparing historic photographs, it was determined that the congregation made a few changes to the church to ensure it was well maintained and with minor modifications to better suit their needs. They added shutters, moved the front door, and painted both the building and the glass to help give the effect of stained glass windows.

Unfortunately, as the Great Depression hit, people began to struggle. With few jobs available and people needing to find work, many folks left Waterford. By 1940 there were only about 75 African Americans living in the area. During this period, the church’s population shrank and was primarily made up of the older generation. As the membership continued to decline, so did the funds. With the needed repairs continuing to grow, the church members had a difficult time maintaining the church. By 1967, the North Carolina-Virginia Conference of the Methodist Church declared the John Wesley Church of Waterford abandoned and sold the site to the Waterford Foundation that following year for $500.

After the church was sold, the descendants of the congregation and the few surviving church members that were left were able to become stewards of the property and continue to use the church to worship. Four months after the Waterford Foundation purchased the property, they transferred ownership to the stewardship committee for $10. The church became known as the John Wesley Community Church of Waterford and was overseen by a Board of Trustees. During this time, the church was used for religious meetings, homecoming celebrations to welcome back past church members that moved away, and an annual fundraising supper. In 1999, before the final member of the board of trustees passed away, he decided to sell the deed for the church to the Waterford Foundation so it could be preserved past his death. The terms of the purchase were that if the descendants were able to form an organization that could maintain the property and be up to the easement holder’s standards, they could buy back the property. In the meantime, the Waterford Foundation would maintain the property. In 2000, the Foundation donated an interior and exterior preservation easement to the Virginia Board of Historic Resources to prevent any inappropriate changes that would alter the historical integrity of the church.

Since the Waterford Foundation acquired the property, they have renovated and restored the church. In 2001, they repaired the steeple and belfry’s framing and replaced and fixed the building’s roof. In 2002, the stone foundation was repointed, window panes and sills were repaired and replaced, steps and a landing were built, and French drains were installed to prevent further water damage. In 2018, the flight of stairs from the sanctuary to the basement was rebuilt, and a kitchenette, bathrooms, and mechanical room were installed. The newly built bathrooms introduced running water to the church for the first time. All repairs were made with the utmost care to ensure that they matched the original features of the church.

The Foundation is currently applying for grant funding to continue the restoration of the sanctuary. They have also been in touch with some of the congregation’s descendants who may be interested in forming a new organization to reclaim the church. The Waterford Foundation looks forward to a day when they will be able to return ownership of the church to the descendants of the original congregation.

Sources:

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “John Wesley”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 May. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Wesley. Accessed 23 May 2023.

- Coffield, Brian, et al. John Wesley Methodist-Episcopal Church Historic Structure Report, Smithgroup, prepared for the Waterford Foundation, 2019