by Jane Williams and Bronwen Souders

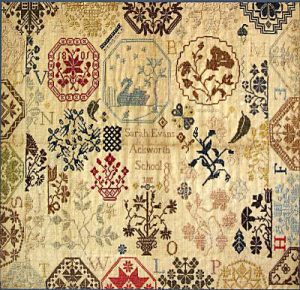

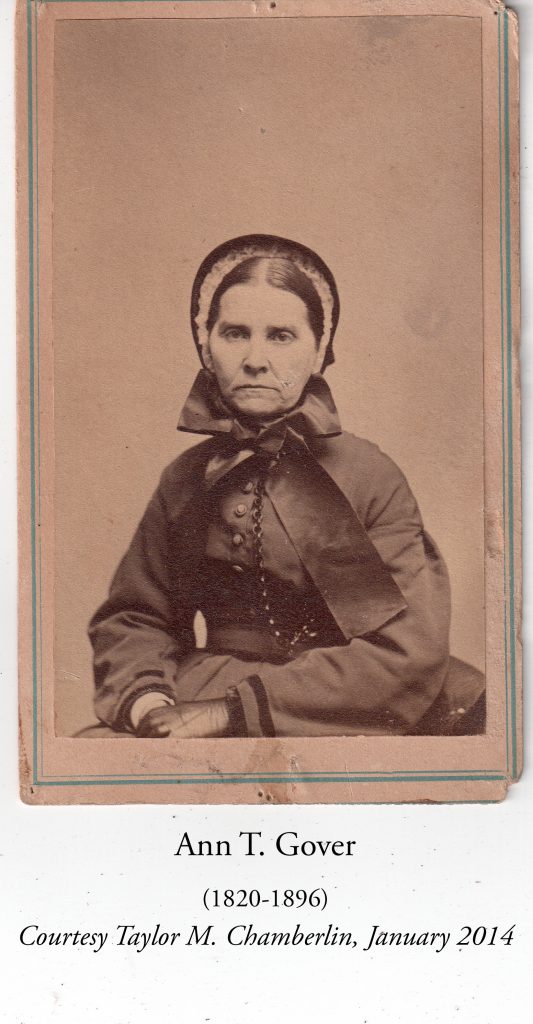

Waterford Quaker Ann Taylor Gover was probably not yet nine when, in 1829, she put down her needle and presented her latest handiwork for inspection. Her cross-stitch sampler evidently passed muster as it remained a treasured keepsake in the Gover family for nearly two centuries. It is now a valued part of Waterford’s Local History Collection, and to a trained eye it has stories to tell.

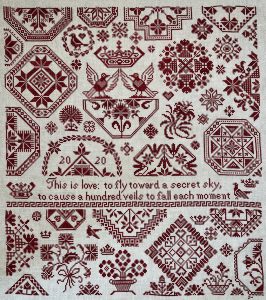

Cross-stitch samplers like Ann’s can tell us much about the cultural context and even artistic aspirations of ordinary women often marginalized in the telling of our history. Ann’s is exemplary of Quaker samplers of the early 19th century. Although the Society of Friends did not put a definite stamp on the artform of quilts, for example, as the Amish did, their samplers have a long prolific history in Quaker art.

One of the most iconic series of samplers come out of the English Quaker school Ackworth in West Yorkshire, UK. The Ackworth School’s are marked by fine and intricate motifs that still influence sampler design today.

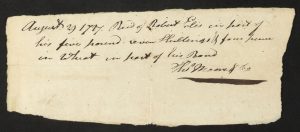

In 1829, Mary B. Randolph stitched the piece below under the guide of Quaker teachers in Redstone, PA. Although Randolph’s sampler is similar to Ann’s, both are unique in their details. Samplers are often described as a teaching tool, but we also now view them as distinct artistic endeavors by the embroiderer. Ann’s piece is lovely and balanced and gives us some insight into everyday life in Waterford’s Quaker community. It includes a central urn, scripted alphabet and intricate border. It was worked in linen with silk thread.

Ann was born into an important Quaker family in Waterford. Her father Jesse had earned prosperity as a harness and saddle maker, dry goods merchant, butcher and hat manufacturer. Both he and his wife Miriam “had received a gift in the ministry” of their Quaker meeting. And Jesse was active in the Loudoun Manumission and Emigration Society, an early effort to ameliorate the condition of Loudoun’s enslaved Blacks.

Ann as a teenager attended Samuel M. Janney’s highly regarded Springdale boarding school in nearby Goose Creek (Lincoln). Janney was Loudoun’s most prominent Quaker. But family fortunes darkened in 1845 when Jesse Gover died, still in his 40s. Ann, as the youngest daughter and still single, evidently set aside any plans of a family of her own to help look after her mother.

In 1871, some years after Miriam’s death, President Grant appointed Samuel M. Janney superintendent of Indian affairs in Nebraska, and, at about 50 years of age, Ann jumped in to help with her old Quaker headmaster’s mission. She set to work at the Manuel Labor School on the Pawnee Reservation, and with a fellow instructor was put in charge of the sewing program. Her childhood skill with needle and thread was thus passed on to another generation in a far-off place.

The circumstances were often trying. “. . . Of the 80 scholars connected with us at the time of our last report, one was a day-scholar, and attendance has been discontinued; five have been married and are now living in their own homes, two were killed by the Sioux, two died of chronic diseases, and one of an epidemic . . . [but] the girls are becoming skillful cooks, laundresses, housekeepers, and seamstresses under the kindly and watchful direction of those who instruct them . . . .”[1]

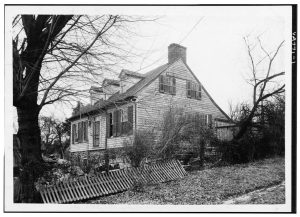

Ann eventually returned to Waterford and lived with her brother Samuel in the Griffith-Gover House on Main Street; she never married. She died in 1896 and rests in the Fairfax Meeting Burying Ground, leaving a childhood sampler that offers a glimpse into the artistic endeavors of everyday life in Waterford and presaged an adventure in the West that was not ordinary at all.

[1] Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Nebraska Superintendency http://images.library.wisc.edu/History/EFacs/CommRep/AnnRep71/reference/history.annrep71.i0011.pdf

Bronwen C. Souders grew up in the American West and in a recent interview said her younger self found history “boring”. The past 50 years living near Waterford have changed her perspective. Now, as she used to say of her friend and mentor, historian John Divine, she is more familiar with the village of the 1820s than of the 2020s. This month’s interview with Bronwen focuses on the A.W. Phillips Meadow pastel, created by

Bronwen C. Souders grew up in the American West and in a recent interview said her younger self found history “boring”. The past 50 years living near Waterford have changed her perspective. Now, as she used to say of her friend and mentor, historian John Divine, she is more familiar with the village of the 1820s than of the 2020s. This month’s interview with Bronwen focuses on the A.W. Phillips Meadow pastel, created by