Personal letters and journals can yield a wealth of information about everyday life during significant periods of history, such as in Waterford during the Civil War. Discovering a trove of correspondence is a boon for historians, as described in the About This Book section of To Talk Is Treason: Quakers of Waterford, Virginia on Live, Love, Death & War in the Southern Confederacy:

This account of Waterford’s Quakers during the Civil War came together unexpectedly in the summer of 1996. While several long-time residents of the village had been familiar with the outlines of the story, many of the details were unknown–and the village had lost touch with descendants of those who had lived through the conflict.

One of those descendants, Miss Phebe Haviland Steer, has miraculously provided the key to unlocking that past. From her home in California, she enquired if anyone in Waterford would be interested in a box of old letters and journals that had belonged to her grandmother, Mary Frances Dutton Steer. They had just been rescued from being discarded by a well-meaning friend.

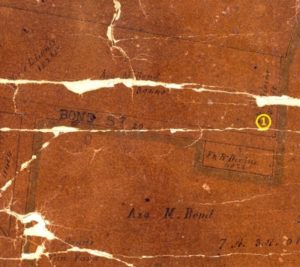

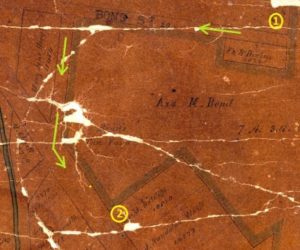

Miss Steer, three years earlier, had generously given the Waterford Foundation an extraordinary patchwork quilt pieced–in the manner Mollie Dutton herself has described–from the silk wedding dress her great-grandmother Emma Schooley Dutton had worn in 1838. The cover of this book reproduces two colors of that quilt.

Waterford is forever in debt of these women. For it turned out that Mollie had preserved a rich record of the past, keeping not only her own wartime letters, but also meticulously copying a large volume of correspondence and other writings of family and friends from the early 19th century to the end of her life. Among those treasures is Rebecca Williams’ poignant diary of the war years.

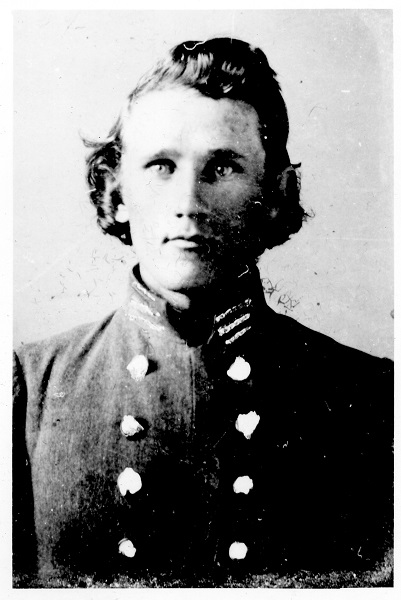

These writings in turn provided clues to other sources. Dutton descendants in New Jersey generously shared period photographs of Lizzie and Lida and Mollie, as well as additional details of their times. A library in Michigan furnished a list in Lida’s hand of Union soldiers who had passed through Waterford. There is every reason to expect that more information will be discovered; it is our hope that this first telling of the stories will spur the search…

In the end what makes this narrative compelling are Waterford’s remarkable Quakers themselves. When disaster struck those peaceful, capable people met the challenge without flinch or compromise. We are grateful that their care in recording their history has given us a chance to know them and their times. May we do as well to preserve what they have left us.

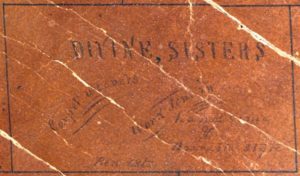

John E. Divine, Bronwen C. Souders, John M. Souders, September 1996

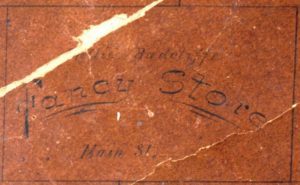

To Talk Is Treason: Quakers of Waterford, Virginia on Life, Love, Death and War in the Southern Confederacy, 1996, WAterford Foundation

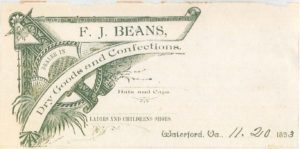

The Waterford Foundation maintains an institutional Archives as well as a Local History Collection. If you may be interested in donating documents, photos or artifacts from Waterford’s past, please reach out to our staff for further information via phone (540-882-3018, x2) or email.