Do you have any more questions about the MARL proposal? Fill out the form with the question below and someone will get back to you!

Do you have any more questions about the MARL proposal? Fill out the form with the question below and someone will get back to you!

The Mid-Atlantic Resiliency Link (MARL) is a collection of new and upgraded power transmission lines aimed at meeting the current and future power needs of the Mid-Atlantic region with improved resiliency against outages and other power interruptions. A portion of the MARL project was awarded to NextEra Energy by PJM Interconnection, the regional transmission authority responsible for regulating energy providers in the Mid-Atlantic region.

The NextEra portion of the MARL project includes a proposed new line through rural parts of Loudoun County from the Daubs substation south of Leesburg, around Leesburg to the west through communities including Hamilton, Waterford, and Lovettsville before connecting to upgraded lines through existing rights-of-way in Maryland.

| Date | Milestone |

| January 2024 | Contract awarded to NextEra Energy; Routing Study Begins |

| May 2024 | Routing Study Complete |

| June 2024 | Stakeholder Meetings and Public Input Sessions |

| late 2024 | NextEra Proposal Submission to Virginia State Corporation Commission |

See NextEra’s project page here.

See an interactive map of the preliminary proposed line here, which includes the proposed NIETC Designation Corridor. (Created by Piedmont Environmental Council, thank you!)

In January 2024, representatives from Loudoun nonprofit organizations, community and neighborhood associations, business organizations and other interested parties gathered at the Old School in Waterford, Virginia to coordinate efforts to oppose the proposed greenfield transmission lines of the Mid-Atlantic Resiliency Link contract awarded to NextEra Energy by PJM Interconnection. Instead, the Alliance believes that all transmission lines should be built in existing power corridors The members of the alliance developed and agreed to the following Declaration to clarify their common purpose (link to PDF Version)–

We, the undersigned stakeholders, representing business, preservation, agricultural, environmental, and community organizations in Loudoun County, Virginia, call upon NextEra Energy to avoid building a new power corridor through rural Loudoun County, in view of the negative impact of such construction on the agricultural community, local economy, heritage and natural resources, and residents of the region.

We strenuously oppose construction of new “greenfield” lines in rural areas of the County. All new transmission lines should be located within existing power corridors – which we understand would be acceptable to PJM.

As currently configured, the proposed route will cause major collateral damage to existing local businesses, notably in the agricultural and tourism sectors, as well as to residential valuations. Power corridors must be sited to minimize the impact on existing businesses, including those dependent on intact open landscapes.

Historic and environmental sites, including landscapes, define the distinctive heritage of Loudoun County. In no instance should power corridors transit through or near National Historic Landmarks, historic districts, and other properties under conservation or preservation easements.

For NextEra, this is a commercial decision, but for Loudoun it’s existential. We call for no new power corridors in rural Loudoun!

Our communications and outreach team can be reached out transmissionlines@waterfordfoundation.org. You can also find them during Foundation office hours from 10am-2pm Tuesday-Friday at 40222 Fairfax Street, Waterford VA 20197, around the county during travelling office hours, or available for appointments.

Abigail Zurfluh- Communications Chair

Abigail is also the Historic Preservation Director for the Waterford Foundation. She has been involved with the Alliance since the beginning meetings at the Waterford Old School. She has a degree in historic preservation and geography from the University of Mary Washington. In her free time, she loves to explore all of what Loudoun County has to offer, playing games (especially board games, card games, or trivia) with friends and family, and line dancing. Her favorite part about Rural Loudoun is the balance of the built and natural environments achieved through historic preservation and environmental conservation.

Alexander Newton- Field Operations Director

Alex joined the communication and outreach team as the Field Operations Director in June 2024. After graduating with a Master’s Degree in History Education from Virginia Tech, he moved back to Loudoun and started teaching at John Champe High School. In his free time, Alex enjoys visiting local businesses, painting miniatures, reading historical nonfiction, and wildlife photography. His favorite part of Rural Loudoun is the local community he is a part of. He loves participating in local events like Oktoberfest in Lovettsville and the Waterford Fair.

Excerpt from Reb and Yank, A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia by Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Souders

Chapter 26: Blockaded; January-February 1864

The New Year found Capt. Albert M. Hunter of Cole’s Cavalry stranded deep in “Mosby’s Confederacy.” Two days earlier, with orders to scout to Rectortown in Fauquier County, he had led sixty men out of his battalion’s winter camp on Loudoun Heights, opposite Harpers Ferry. They started on the road to Hillsboro in late afternoon but, aware that Rebels maintained lookouts atop outcrops on the Short Hill and Blue Ridge, Hunter disguised his plans by cutting back across country after dark to seek shelter among Lovettsville’s Unionists.

Leaving the German Settlement on the last day of December, the Marylanders pushed on through sleet and snow to a farm two miles outside Upperville, where they spent their second night. A brief skirmish the following morning confirmed that the enemy knew of their presence, but Hunter felt compelled by his orders to proceed into Fauquier. Riders shadowed his movements along the way and, after sending an advance party to briefly reconnoiter Rectortown, the apprehensive captain ordered his men to return directly to Harpers Ferry.

His concern was warranted. Although Mosby was out on a scout, a subordinate, Capt. William R. Smith (Co. B, 43rd Va. Cav.), sounded the alarm for the partisans to assemble. Their number surpassed 35 by the time they reached Rectortown, but the Yankees had already left. Galloping off in pursuit, the Rebels caught up with their quarry at a crossroads four miles to the north. A running fight ensued that continued almost to Middleburg, where Hunter’s troopers broke ranks and began to flee in confusion. At this point the captain was thrown from his saddle and taken prisoner. Left unattended while his captors went to retrieve his horse and equipment, he concealed himself in the underbrush and escaped detection on their return.1

The captain emerged from hiding that afternoon and set off on foot toward the Union lines along the Potomac, thirty miles away. His first obstacle, Goose Creek, was so swollen with slush and ice that he could not wade across. Skirting its banks, Hunter stopped at a small log cabin after dark, where he obtained food and an old hat to ward off the bitter cold. But no amount of persuasion, or offers of payment, would induce the fearful tenant farmer to guide him to safety. “I dare not do it, my boss would know before sundown tomorrow and I would have to go into the army.”

Armed with directions from his reluctant host, Hunter pressed on alone to Pot House, a crossroads north of Middleburg, where he spotted a horse tied to a gatepost. Concluding it safer to “play infantry” than ride, he passed by – a fortunate decision he later learned, as the steed belonged to Mosby himself. As the night wore on, Hunter lost his way and again risked seeking help rather than freeze to death. This time, he walked up a lane to a substantial house that signified a well-to-do farmer. Things got off to an inauspicious start when the door was opened by “an old negro woman,” who answered “No sah,” when asked whether her master was Union man. Still there appeared to be no choice but to identify himself when the owner appeared and explain his predicament. Like the man in the cabin, his new host knew about the fight earlier in the day and informed Hunter that not more than half of his men had managed to escape, “which was the truth, as [the captain] afterward learned.” The secessionist farmer agreed to provide directions to the Goose Creek Meeting House, but only if the officer would sign an order enabling him to purchase supplies at Point of Rocks. An agreement was reached, and Hunter filled out the necessary authorization, while his host outlined the best way to reach the Quaker community.

The weary Yank finally staggered into Goose Creek at sun-up, seeking refuge in the first house he came to. Although put off by his scruffy appearance, a Quaker woman allowed him to enter and take some breakfast. The captain then fell into a deep sleep until roused in the afternoon by a man named Steer, who offered to drive him to Waterford. To hide his uniform, Hunter was given gum overshoes and an old gray overcoat, which along with his battered hat, gave the appearance of a common laborer catching a ride. At Hunter’s suggestion, Steer drove him to John Dutton’s home in Waterford. The exiled shopkeeper had returned to spend the New Year with his family and was well acquainted with the captain. Once, the two had tried to skate on the canal from the Point to Georgetown, only to be forced back by rough ice. Even so, Dutton did not recognize the strange-looking man in the carriage until Steer identified him. Seeing an opportunity to play a joke on his family, he invited the two in, but told Steer to introduce his companion, still in disguise, merely as a “friend.” The visitors were in the parlor conversing with the family for a half hour before the youngest daughter (11-year-old Annie) finally recognized their guest. After supper and a night’s rest at the Duttons’, Hunter resumed his disguise and was driven to the Point by Steer. Not wanting to offend his benefactor by offering money, the captain presented him with his spurs and left a fine pocket knife in the carriage. His arrival by train at Harpers Ferry caused quite a stir, as he had been reported wounded in the fight at Middleburg.2

Read more from Captain Hunter at the Emmitsburg Area Historical Society website.

PJM, a regional transmission organization, has accepted a proposal for new power transmission lines that would go through Western Loudoun and directly through the Waterford National Historic Landmark to support the needs of the data center industry. The proposed 500KV lines go directly through conserved land and land under easement with the Virginia Outdoors Foundation. These transmission lines pose a major threat to the integrity of the Landmark and the region we sit in. Our Landmark status is intrinsically linked with the unspoiled viewshed surrounding our historic village. Not only that, but every resident and business who calls Waterford home would be impacted by the construction of these power transmission lines. The Waterford Foundation stands opposed to such violation of our conservation values, and will work to oppose any impact to the integrity of Waterford’s Landmark status.

Why is this important? Western Loudoun has remained relatively untouched by the massive growth of the data center industry in the past years. Instead, it remains a haven for farmland, open spaces, conservation, and preservation. Amongst the picturesque hills sit wonderful and profitable businesses and organizations that rely on the surrounding. It is also an area where history and past of Loudoun County can be found woven into the hustle and bustle of 21st century life. The best example of this can be found in the National Historic Landmark of Waterford. Building transmission lines through this region would impact the daily lives of residents in an unprecedented manner; damage the livelihoods of farms, businesses, and organizations that are in its path; and damage the integrity of the Waterford National Historic Landmark. This is similar to a proposal to put transmission lines through Gettysburg National Battlefield or Mount Vernon.

We need your support to fight this threat. One thing that the Foundation has learned is the power of the Loudoun County community banding together for a common cause. Please see below for ways you can help us oppose this threat.

The Waterford Foundation is maintaining an email list for those who would like to stay informed about this issue. If you would like to be included, please email Historic Preservation Director Abigail Zurfluh here, or fill out the form at the bottom of this page.

Share your concerns with decision makers:

National Interest Electric Transmission Corridor (NIETC):

Virginia State Corporation Commission:

Elected Officials:

Spread the word about this issue:

Show your support by signing our online petition:

Donate to support the Waterford Foundation’s work to preserve the Waterford National Historic Landmark and oppose threats like this.

February 2nd- Due Date to Submit Public Comments on Stage One of National Interest Electric Transmission Corridor to the DOE. Public comments can be submitted via email to NIETC@hq.doe.gov

February 7th at 6:30pm- Loudoun Nonprofit Leadership Summit is taking place at the Old School in Waterford. If you are a leader/staff member of a preservation, conservation, or other related organization/stakeholder in this issue, please RSVP using this link.

May/June: Possible completion of NextEra routing study

Summer 2024: Be on the look out for community open houses hosted by NextEra about the routes.

Late 2024: Possible aim for a proposal to SCC

Background Information: Our colleagues at Piedmont Environmental Council have been monitoring PJM’s transmission line proposals for some time. Visit their page to view a map of the proposed path and learn more about the issue. Linked here is a video made by our collogues at the Piedmont Environmental Council providing important background to this issue. Running time is roughly eight minutes.

NextEra Information: Read more about the Mid-Atlantic Resiliency link from NextEra at their website here. Specific questions, comments, or concerns can be sent to the NextEra team using the email box on the webpage. Currently, NextEra is working on the routing study through a third party.

Loudoun County Government Role: Read more about the role of the Loudoun County government in this civic alert.

National Interest Electric Transmission Corridor: Read more about the designation process here.

In the News:

Opposition Letters:

Other letters:

Other Resources:

December 5th, 2023: PJM Transmission Expansion Advisory Committee (TEAC) meets to review proposals for the Regional Transmission Expansion Plan (RTEP). See public comments associated with this meeting here. Thank you to those who sent letters of opposition!

December 11th, 2023: PJM Board approves the slate of proposed projects, including the proposal from NextEra to construct a new greenfield transmission line through the Waterford National Landmark. See details in the PJM whitepaper, here.

December 13th, 2023: Loudoun County Board of Supervisors met to adopt a new zoning ordinance in Loudoun County that includes new approval processes for data centers in Loudoun County.

December 17th, 2023: People gathered together in the Old School to celebrate the 20th Anniversary of Conservation on Phillips Farm. It was a fun evening full of celebration and reminiscing. Thank you to everyone who was able to attend!

In the early 1900s, Christmas was an occasion when Waterford residents of different congregations came together to celebrate. According to recollections by late Waterford resident John Divine (1911-1996) in When Waterford and I Were Young:

“All three churches [The Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist, still standing on High Street in Waterford] shared in a Wednesday evening prayer meeting and all three had Sunday School picnics. The reward for going to Sunday School was two-fold: the picnic, when ice cream flowed abundantly, and the Christmas program, when we got an orange and a small box of chocolate drops.

The Christmas program also gave all of us amateur actors a chance to perform. Any similarity between our Three Wise Men and the real Magi was purely coincidental. Only the parents enjoyed that group of squirmy little boys singing Away In A Manger off key.”

Many holiday recollections center around special foods and feasts among family and friends. Divine remembers the special foods that came to Waterford during the holidays in the early 1900s, sold out of the meat shop operated by E. L. James and later his son Minor out of the Old Insurance office on Second Street:

“At Thanksgiving and Christmas, the meat shop handled oysters. The only time I ever ate oysters was at those two dates: at $6.00 per gallon, they were a real delicacy. Orders were placed about ten days in advance and they were received a day or two before the holiday. The gallon cans, packed in ice, were shipped up on the railroad to Paeonian Springs. Later, when Minor James got a Model T truck, he would drive to the wharf in Washington, D.C. to get them.”

When Waterford and I Were Young is available for purchase online or in person at our offices in the Old School.

Written by Robert Dabney Trussell. This article first appeared in the 50th Annual Waterford Homes Tour and Crafts Exhibit Booklet, October 1-3, 1993.

The American Civil War–it has been described variously as the war between the states; the conflict that pitted brother against brother; the battle for freedom or slavery.

It was a war of extreme points of view where the middle ground of rationality was razor thin or lost in the bloodletting. It was a war of opposing armies marching, foraging, camping and fighting over the rolling fields and idyllic towns of a new republic. The war involved every community in some way and likewise touched every citizen in the nation.

While most Americans both North and South marched to the cadences of their causes, Quakers in both regions struggled to heed their consciences. For the most part, members of the Society of Friends believed that both governments were wrong to use violence to settle their differences. Quakers opposed slavery as the vilest form of human degradation, superseded only by the act of killing.

Friends generally stood against a war that most Americans, religious denominations and political organizations of the time regarded as a righteous war. How could Quakers take such a stand?

The simplest reason stemmed from a primary precept of the Quaker faith that the light of God burns within every man, woman and child. Therefore, the sacredness of life was not to be violated in any manner. This moral stance had a secular human rights component that faulted both the Union and the Confederate governments. Friends found the federal government’s brutal policy toward Native Americans to be as inhuman as the South’s institution of slavery. Also, Quakers openly decried the North’s abolitionist propaganda while its manufacturers profited greatly from raw goods derived from slave labor.

At the same time, the Civil War altered the traditional isolationism of the Friends and thrust many Quakers into the turmoil of the time.

Even before the war, some Quakers risked their lives as participants of the “Underground Railroad” which provided a route to freedom for thousands of slaves. Quakers, even in the South, attacked slavery through newspaper articles, tracts, and nationally published Quaker journals. When hostilities did break out in 1861, numerous Quakers struggled greatly with their consciences, left their meetings for worship and took up arms against the Confederacy.

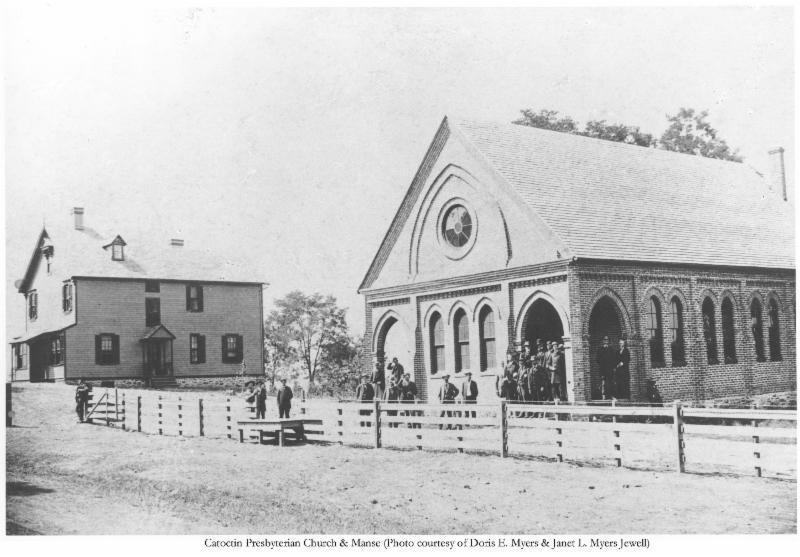

Quakers in the South and thereby in Loudoun County, found themselves at particular risk. This population of Friends was sizable, influential and prosperous. Following the land migrations of the 17th and 18th Centuries, Quakers settled throughout Virginia. More than 60 meeting houses were built in the Commonwealth and several Quaker communities were well established in Loudoun County. The town of Waterford became a major center for Quaker education and commerce, as well as the location of the Fairfax meeting.

This whole community of Friends was threatened by the war. Whereas Quaker pacifism was protected in the North (Abraham Lincoln’s great-grandfather was a Pennsylvania Quaker), being a Quaker in the wartime South was a liability.

Quaker men who refused to enlist or answer the draft were frequently imprisoned and ridiculed. One Waterford Quaker objector was even abducted from his home, forced to march with an infantry unit and cruelly placed without defense in the front line of an attack during a battle. Somehow he survived that ordeal only to die from disease in a Confederate prison. The Fairfax Friends’ opposition to slavery left them vulnerable to discrimination or at least shunned by fellow Southerners. Rebel armies would target Quaker farms in the area for food and shelter. Farmers and merchants suffered great loss of property and business. Also the war cut off Quakers from their friends and relatives in the North.

Through it all, Friends in Loudoun County kept their faith and traditions alive and struggled to follow Christ’s words “to do unto others”. A poignant example of this belief is found in a letter written in 1863 by Susan Walker, a Waterford Quaker.

Susan Walker described an event that occurred early in the war. On Sunday, Friends of the Fairfax meeting arrived for worship to discover a company of Confederate regulars billeted in the stone meeting house. Both the house and the yard were strewn with stacks of rifles, flags and campaign gear. Soldiers relaxed on the meeting house benches and slept up in the gallery. As the Quakers entered, some soldiers rose to meet them with jokes about their plain attire and taunts about their anti-slavery beliefs.

But the Quakers were resolved to worship that day; a quick compromise was reached with the commanding officer. A portion of the meeting room was partitioned off with tenting allowing the Quakers a place to quietly wait upon God. The Quakers then invited the soldiers to worship with them. Curious about “how Quakers prayed”, several of the company joined them. During the silence, an elderly woman, moved by God’s presence, stood and spoke to the odd assembly. In a strong voice she prayed “God bless all here and that the wings of peace might return to our prosperous country and peace be with the strangers in our midst”.

With this the woman sat. So moved by her words, the soldiers wept openly: “…great tears coursed each other down their sun-burned cheeks”, wrote Susan Walker.

The year was 1861. Four long and bloody years of the Civil War still remained before peace finally returned to the Quakers of Waterford and the Nation.

Contributor: Robert Dabney Trussell who attends Goose Creek meeting in Loudoun County. Mr. Trussell lives in Rosemont, Maryland and works for the AFL-CIO in Washington, D.C.

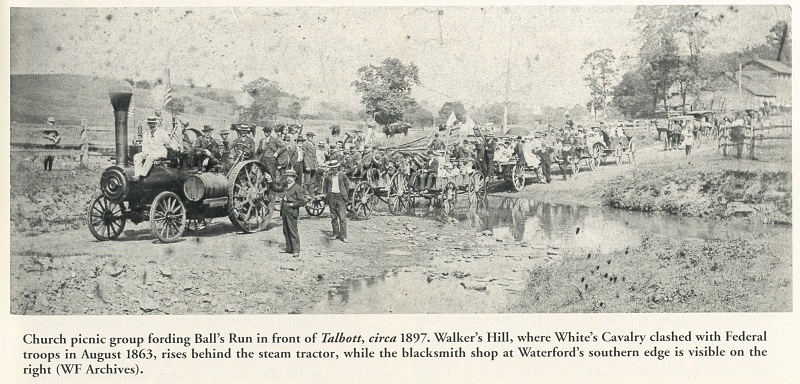

The most significant Civil War action to take place in the Waterford vicinity occurred in early August 1863 when Eliiah White’s 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry encountered a large scouting party from Harpers Ferry commanded by Capt. Harvey H. Vinton at Walker’s Hill at the southwest corner of the Town of Waterford. The following is an excerpt about the skirmish and its aftermath from Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia by Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Souders:

Brig. Gen. Henry H. Lockwood’s earlier request for cavalry to contend with partisans in Loudoun County remained unfilled, but the Harpers Ferry commander still had 400 horse soldiers at his disposal: specifically, detachments from Purnell’s Legion, the 1st Connecticut and the 6th Michigan. Accordingly, on 6 August he ordered Col. George Wells to send out a hundred-man cavalry detachment from the 1st Brigade with instructions to pass through Hillsboro and Waterford as far as Leesburg. The objective was to “ascertain the force and whereabouts of…. Rebel guerrillas who are reported to be ranging Loudoun County and committing depredations on the persons and property of the Union citizens thereof.” The next day thirty riders from the 1st Connecticut and seventy from the 6th Michigan crossed the Shenandoah into Loudoun with three days’ rations for an extended scout in pursuit of White’s “guerrilla band.” The column, led by Capt Hervy H. Vinton of the Sixth’s Co. M, proceeded up the Between the Hills valley as far as Hillsboro, turned east through the gap in the Short Hill and arrived at Waterford in the late afternoon.

That same morning (7th) their intended quarry, Colonel White and about 120 men of the 35th Battalion, rode into Wood Grove, where they learned that Vinton’s column was in Hillsboro, three miles distant. Cautiously approaching that town, the Rebels found the Yankees had already departed for Waterford. White followed the bluecoats east, halting his command halfway between Wheatland and Waterford near the farm of Armistead Vandevanter. He assumed the Federals would return to Harpers Ferry via the same route later in the day and laid an ambush. Just before dark, however, word arrived that Vinton planned to spend the night at Waterford. At this point White edged his men closer to their target, cutting across Sanford Ramey’s farm (Rosemont) to the south branch of Catoctin Creek, then moving downstream toward the town, using trees along its banks as cover.

The Northern squadron had been in Waterford about two hours when Vinton learned that White and “his band” were only a half mile away, observing their movements. With darkness fast approaching, the Michigan captain moved his 100 riders to a more defensible “high hill” on James Walker’s farm, one that overlooked the town from the southwest. The Federals posted pickets on all roads and paths into town, and about 9 p.m. set out additional “camp guards” around the encampment at a distance of 10-15 rods. A Connecticut trooper recalled the memorable evening.

All remained quiet until near 11 o’clock, when the enemy was discovered marching out of the woods into an open field, evading our outer pickets, but was discovered by one of the camp guards, who, according to instructions, fired his pistol and reported to the commanding officer that the enemy was approaching. The men were immediately aroused from their slumbers, mounted their horses, and, according to orders from Capt. Vinton, fell in line back towards the advancing column, the Michigan cavalry being on the right and the Connecticut on the left.

The rebels came slowly and steadily up the hill until our boys could hear the officers saying to them stead men, keep your dress, etc. They, however, did not make a good calculation, for in charging their left came in contact with our left, therefore the Michigan cavalry did not receive a shot.

Receiving no orders from the commanding officer, Sergeant Gore gave the order, “Form left around wheel,” but before our boys were in line, the rebels gave a volley, wounding several horses. This made them very fractious, and uncontrollable, three of which charged through the rebel line. Our boys then gave them a splendid volley, which checked them. At this point if the officers had brought the Michigan men around and charged them on their left flank, it would have totally routed and put them to flight. But no! All this time the officers and men were looking the other way for them, but finding they were attached in the rear broke and ran, disgracefully leaving only thirty men to contend against 300 strong.

The rebels then rallied and our boys were compelled to fall back, leaving in their hands ten men, who fought most gallantly. If the Michigan boys had shown half the courage that Frank Leslie’s artist gives them credit for at Falling Waters, we are satisfied the result would have been very different.

Frank Myers’s account of the fight on Walker’s Hill provides a different perspective. After ascertaining the location of the enemy’s hilltop camp just before dark, White had his men tie their horses along the creek and follow him. With the goal of taking as many horses and prisoners as possible, he told the dismounted soldiers to observe strict silence until they reached the edge of the camp. The field below the hill was filled with haycocks, which made it difficult for the Rebel colonel to keep his men in line. Then, still 200 yards from their objective, White stumbled over one of the obstacles and accidentally discharged his revolver. This caused further confusion, some thinking it was the signal to open fire, others believing they were under attack. By this time the Yanks had mounted and fired one volley at the shapes approaching in the dark, before departing “with all haste.” The Southerners returned fire, felling three or four of the enemy. But most of the Federals made good their escape, with all but a few of their horses.

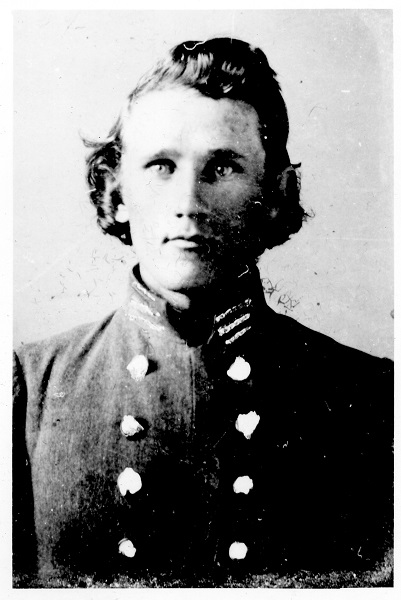

The engagement proved costly to the 35th Virginia. Pvt. John C. Grubb was killed in the initial firefight, and his cousin, Capt. Richard B. Grubb of Company C, was mortally wounded nearby in a confrontation with Yankee pickets on the road to Hamilton. Myers considered the loss “irreparable,” calling Captain Gurbb “one of the best, if not the very best officer” in the battalion. He termed the “affair” at Waterford “fruitful only in disaster.”

Rebecca Williams was spending the night with the Walkers when the fight broke out at the western edge of the farm. “I had not slept any when about 11 o’clock, I heard musketry very sharp firing for 4 or 5 minutes. White & his gang attacked the Federals, they fell back in order, retired down street, again formed in line of battle on A[masa] Hough’s hill [at the north end of town], but they were not pursued….” In fact, White’s dismounted troopers were in no position to pursue their foe even if they had wanted to. Rebecca later learned that each side had suffered two killed, but thought there might have been additional Confederate losses. The “two Grub[b]’s were taken to E. Walker, & from there their freiends conveyed their lifeless bodies home near Hillsborough. The two Federals were brought to the brick [Baptist] church, coffins made & were decently interred. Another badly wounded was brought to Kitty Leggett’s where he is being kindly cared for & is likely to recover.”

At dawn the following morning, as Lida Dutton was returning from an inspection of the skirmish site, she encountered Michigan cavalryman Ulrick Crocker crossing the street at the south end of town. The girl had seen Rebels about on her way out to Walker’s Hill, so she led the soldier back to her parents’ house via an alley to prevent his discovery. On their way, Crocker told how he had lain all night in a cornfield beside his dying companion, Dallas Dexter, whose body Lida had already encountered lying along the road. Crocker had spiked the dead man’s gun and told her that she could keep it as a souvenir, if she could find it. (Lida retrieved the gun and years later presented it to her daughter.) Another soldier, Edward M. Woodward of the 1st Connecticut, also found refuge in the village, and the two Union soldiers were subsequently spirited to safety at Point of Rocks.

In the aftermath of the fighting, one Waterford civilian managed to aid the Union cause while trying to turn a profit. William Densmore, a native of Maine, was a carpenter by trade, but with work scarce in wartime, he sometimes made ends meet by carrying mail between Waterford and Point of Rocks. Like many other residents, he went out to survey the scene of the fighting the night before. His return route took him down by the creek where he found three Rebel horses still tied to the trees. Densmore hired three local black men, Thomas Robinson, French Clapham and George Lewis, to ride the mounts to the Point and turn them over to Captain Means. They had not gone far when they discovered White’s soldiers in hot pursuit “By hard riding and dodging” the trio made good its escape and delivered the horses.

The skirmish on Walker’s Hill was Waterford’s largest engagement of the way. Yet the only account to appear in the Official Records was written at Point of Rocks the following morning by Captain Means, who played no part in it. Captain Vinton had just ridden in to report being attacked by a “large force of rebels,” and that 50 of his men were still missing. (Most would eventually find their way across the Potomac.) For reasons of his own, Means forwarded the information to Washington rather than Harpers Ferry, where Vinton’s expedition had originated. As he had in several earlier messages, the Ranger captain direly warned of Confederate forces massing in Loudoun in preparation for a raid into Maryland. “Send me the force, and I will clean them out. Strangers cannot find them.” Means may have been secretly pleased that Lockwood’s first significant venture into Loudoun had failed, particularly since the general had not seen fit to ask his Rangers to guide the expedition.

Read more about this and other Civil War action in Loudoun County in Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia by Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Souders available online here.

Email: oldschool@waterfordfoundation.org

Phone: 540-882-3018

Privacy Policy