Excerpt from Reb and Yank, A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia by Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Souders

Chapter 26: Blockaded; January-February 1864

The New Year found Capt. Albert M. Hunter of Cole’s Cavalry stranded deep in “Mosby’s Confederacy.” Two days earlier, with orders to scout to Rectortown in Fauquier County, he had led sixty men out of his battalion’s winter camp on Loudoun Heights, opposite Harpers Ferry. They started on the road to Hillsboro in late afternoon but, aware that Rebels maintained lookouts atop outcrops on the Short Hill and Blue Ridge, Hunter disguised his plans by cutting back across country after dark to seek shelter among Lovettsville’s Unionists.

Leaving the German Settlement on the last day of December, the Marylanders pushed on through sleet and snow to a farm two miles outside Upperville, where they spent their second night. A brief skirmish the following morning confirmed that the enemy knew of their presence, but Hunter felt compelled by his orders to proceed into Fauquier. Riders shadowed his movements along the way and, after sending an advance party to briefly reconnoiter Rectortown, the apprehensive captain ordered his men to return directly to Harpers Ferry.

His concern was warranted. Although Mosby was out on a scout, a subordinate, Capt. William R. Smith (Co. B, 43rd Va. Cav.), sounded the alarm for the partisans to assemble. Their number surpassed 35 by the time they reached Rectortown, but the Yankees had already left. Galloping off in pursuit, the Rebels caught up with their quarry at a crossroads four miles to the north. A running fight ensued that continued almost to Middleburg, where Hunter’s troopers broke ranks and began to flee in confusion. At this point the captain was thrown from his saddle and taken prisoner. Left unattended while his captors went to retrieve his horse and equipment, he concealed himself in the underbrush and escaped detection on their return.1

The captain emerged from hiding that afternoon and set off on foot toward the Union lines along the Potomac, thirty miles away. His first obstacle, Goose Creek, was so swollen with slush and ice that he could not wade across. Skirting its banks, Hunter stopped at a small log cabin after dark, where he obtained food and an old hat to ward off the bitter cold. But no amount of persuasion, or offers of payment, would induce the fearful tenant farmer to guide him to safety. “I dare not do it, my boss would know before sundown tomorrow and I would have to go into the army.”

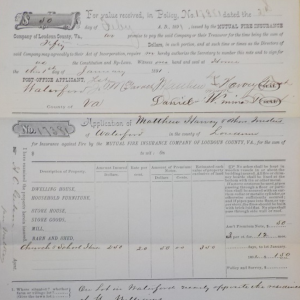

Armed with directions from his reluctant host, Hunter pressed on alone to Pot House, a crossroads north of Middleburg, where he spotted a horse tied to a gatepost. Concluding it safer to “play infantry” than ride, he passed by – a fortunate decision he later learned, as the steed belonged to Mosby himself. As the night wore on, Hunter lost his way and again risked seeking help rather than freeze to death. This time, he walked up a lane to a substantial house that signified a well-to-do farmer. Things got off to an inauspicious start when the door was opened by “an old negro woman,” who answered “No sah,” when asked whether her master was Union man. Still there appeared to be no choice but to identify himself when the owner appeared and explain his predicament. Like the man in the cabin, his new host knew about the fight earlier in the day and informed Hunter that not more than half of his men had managed to escape, “which was the truth, as [the captain] afterward learned.” The secessionist farmer agreed to provide directions to the Goose Creek Meeting House, but only if the officer would sign an order enabling him to purchase supplies at Point of Rocks. An agreement was reached, and Hunter filled out the necessary authorization, while his host outlined the best way to reach the Quaker community.

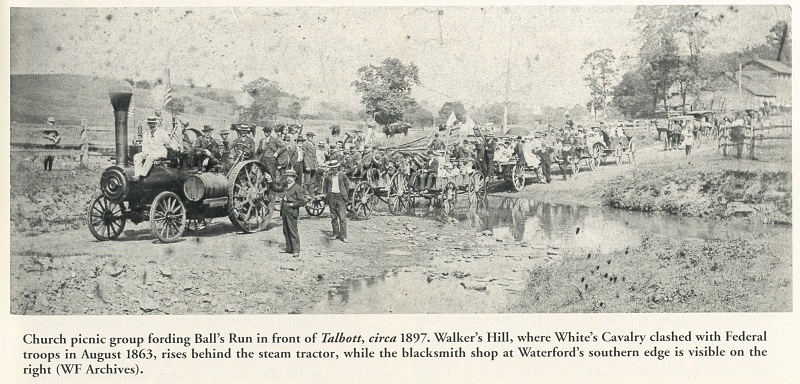

The weary Yank finally staggered into Goose Creek at sun-up, seeking refuge in the first house he came to. Although put off by his scruffy appearance, a Quaker woman allowed him to enter and take some breakfast. The captain then fell into a deep sleep until roused in the afternoon by a man named Steer, who offered to drive him to Waterford. To hide his uniform, Hunter was given gum overshoes and an old gray overcoat, which along with his battered hat, gave the appearance of a common laborer catching a ride. At Hunter’s suggestion, Steer drove him to John Dutton’s home in Waterford. The exiled shopkeeper had returned to spend the New Year with his family and was well acquainted with the captain. Once, the two had tried to skate on the canal from the Point to Georgetown, only to be forced back by rough ice. Even so, Dutton did not recognize the strange-looking man in the carriage until Steer identified him. Seeing an opportunity to play a joke on his family, he invited the two in, but told Steer to introduce his companion, still in disguise, merely as a “friend.” The visitors were in the parlor conversing with the family for a half hour before the youngest daughter (11-year-old Annie) finally recognized their guest. After supper and a night’s rest at the Duttons’, Hunter resumed his disguise and was driven to the Point by Steer. Not wanting to offend his benefactor by offering money, the captain presented him with his spurs and left a fine pocket knife in the carriage. His arrival by train at Harpers Ferry caused quite a stir, as he had been reported wounded in the fight at Middleburg.2

- Albert M. Hunter, “Account of the War Between the States,” part II; Mewborn, In Mosby’s Command, 14-7; Maj. Mosby’s report 4Jan64, OR, 33:9; and Keen and Mewborn, 43rd Battalion, 98-9. Hunter mistakenly placed the initial skirmish at Middleburg. He also recalled losing half of his 60 men, whereas Mosby estimated Hunter’s force at 78, of whom 58 were casualties, a figure Mewborn reduces to 39. ↩︎

- The driver was probably William B. Steer, 69, an abolitionist elder of Fairfax Meeting and husband of Quaker minister Louisa Steer. Hunter was fortunate to reach safety; three of his men were captured near Waterford on 2 January, while making their way back to Maryland (Williamson, Mosby’s Rangers, 118-9). ↩︎

Read more from Captain Hunter at the Emmitsburg Area Historical Society website.